This post is long overdue.

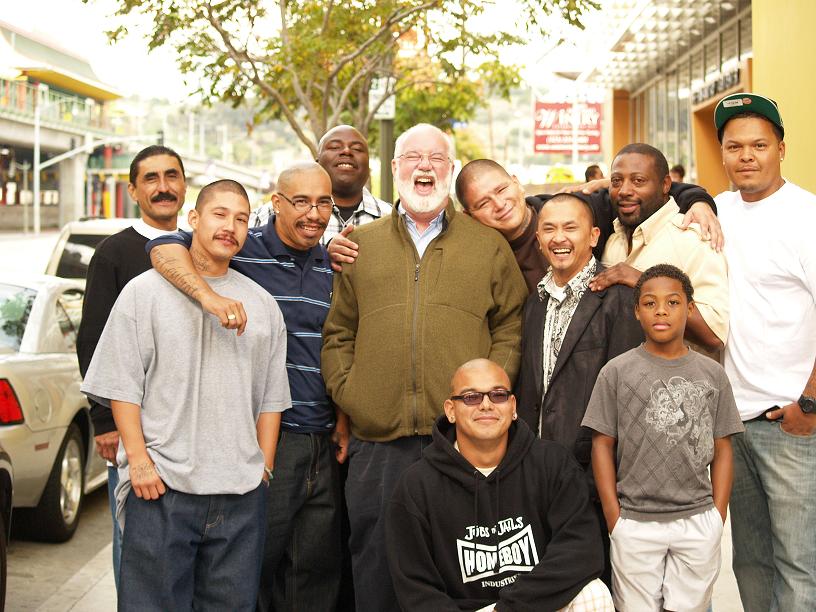

It was at our Thanksgiving dinner table in 2021 when I first heard about Father Gregory J. Boyle, S.J., his work at Homeboy Industries, and a book he wrote chronicling select experiences and teachings called Tattoos on the Heart. The recommendation to learn more about Fr. Greg’s ministry was compelling, so it wasn’t long before I picked up a copy of the book and began my study.

I could not remotely begin to describe the impact that Fr. Greg’s teachings have had on my life in the years since that Thanksgiving conversation. To date, he has written three more titles of a similar flavor: Barking to the Choir, The Whole Language, and Cherished Belonging. While it is true that each book reads in a similar tone, and Fr. Greg certainly has a style and message he adheres to unwaveringly, the teachings and principles within them are equally poignant and powerful with each iteration. That said, the purpose of this post is not to highlight certain ideas or impactful anecdotes — that would take too long, and I couldn’t possibly do the topic justice or communicate the depth of my feelings about what I have learned. Rather, I want to highlight an experience I had that I want to remember for a long time.

On June 26, 2024, I paid a visit to the headquarters of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, California while on a family trip in the area. In what occupies an entire city block in the heart of Chinatown, Homeboy Industries bills itself as the largest gang rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world. Fr. Greg, who is a Catholic priest of the Jesuit order, grew Homeboy from other mission and ministry experiences, and “for over 30 years, [Homeboy has] stood as a beacon of hope in Los Angeles to provide training and support to formerly gang-involved and previously incarcerated people, allowing them to redirect their lives and become contributing members of our community.”1 Having studied and thoroughly enjoyed Fr. Greg’s published writings to that time, and having followed the organization closely on social media, I decided I would make the drive from Newport Beach up to LA and experience for myself the special spirit said to abide at Homeboy Industries. So, I booked my tour a few weeks in advance, and when that morning finally arrived, I made the hour-or-so drive up the I-5 to a place I otherwise never expected to be.

When I got there, I parked a few blocks away and walked to the famous yellow building on Bruno Street. There were all kinds of characters loitering around — characters that I probably would have avoided in any other context. I expected this. But I didn’t feel afraid. At first I got a little lost, not knowing where to go to check-in for my scheduled tour. I wandered back and forth between a few places hoping to get a clue, clearly standing out first as a white guy and second by wearing an Angels cap deep in Dodgers territory. I finally approached the front desk in the main building (which they call “The Well”), told them I was there for a tour, and then I was escorted by one of the homies (the people that work and hang around Homeboy Industries are called homies) to another building where someone finally acknowledged that I was there for a tour. He told me to go back to the main building and join another tour group as soon as they were ready.

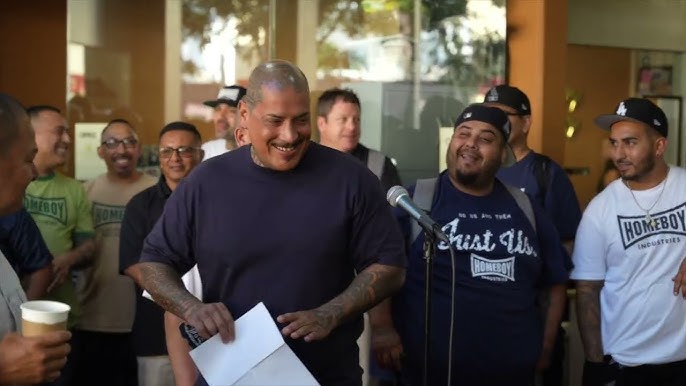

In the main building, they had just started what I learned is an important ritual at Homeboy called the “Morning Meeting.” This meeting is similar to a regular morning standup meeting any organization would have, combined with an inter-faith religious devotional. Everyone gathers in the lobby of the building, filling the floor and the staircase and the upper balconies. A leader at Homeboy had a microphone and was going over some details about the day. The items of business were standard. Calendar items, FYIs, PSAs, etc. But it soon turned personal in what became my first exposure to what I thought I was seeking from my visit. A group of homies formed around the guy with the microphone. He told everyone that the group had recently completed some vocational training in the culinary arts, and he handed each of them a certificate as well as a nice new set of chef’s knives to use in their new employment. It’s funny how in any other context, these were individuals you probably would not have wanted to be handed a set of sharp knives. But now, in their healing and progress thanks to the programs at Homeboy, the knives represented the start of a new life away from the streets and crime of their pasts and toward self-reliance, self-respect, stability, and hope.

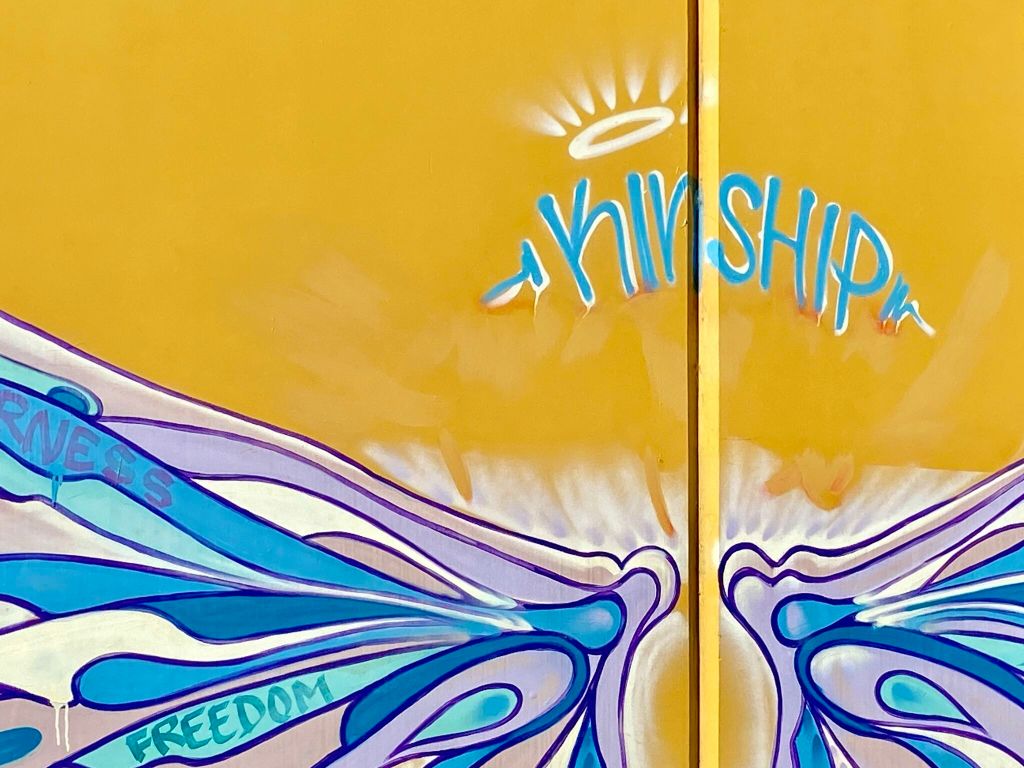

After the cooks’ turn, a young lady approached the microphone with a folded piece of paper in her hand. She held up the paper. “Do you all know what this is?” she asked us. Those apparently familiar with this woman showed their affirmative enthusiasm with whooping and callouts. “This is a letter I got yesterday from the state that allows me to see my kids again,” she said. The place erupted in cheering and applause. She became emotional, and the homies took turns embracing her. It was a victory after almost certainly a long fight, and everyone was celebrating. It was a powerful moment with the kinship Fr. Greg is always talking about on full display for everyone.

Someone then took the mic and said it was time to pray. A hush spread across the room. Hats were removed, signs of the cross were made, and a young man began to pray. The incredible thing about uniting in prayer with people that don’t go to the same church as you or follow the same traditions as you is that how something is said loses importance entirely compared to what is said. As a Latter-day Saint from Utah with a robust belief in the Holy Ghost (the Spirit of God) and its witness of holiness and truth, I felt an abundance of light and love fill the room in that moment as the homie from the projects in LA prayed in his way for God to watch over all of us and bless us on our paths. I couldn’t help but look around the room during the prayer and marvel at the diversity and reverence present. Knowing a little about the individuals that hang around the Homeboy campus from reading Fr. Greg’s books —the people surrounding me on all sides— I had an idea of the pain and suffering the majority had experienced or were experiencing. I contemplated my own experiences and felt humble and grateful. I felt a lot of love for my neighbor in that moment, and I felt safe. It was a beautiful prayer, and I made sure to utter a spirited “amen” at the end of it.

When the Morning Meeting adjourned, I followed a group of people that looked like visitors out the back to the courtyard where they were assembling the tour groups. I ended up joining a couple visiting from the Midwest. “Carlos!” someone near us shouted. “You wanna take this group around?” Carlos walked over. He would be our tour guide. Carlos was a diminutive figure, late fifties maybe (noticeably older compared to most of the older homies around). He was wearing dark sunglasses and a black Dodgers cap. We followed him back into the main building as he asked us some basic questions. “Salt Lake City” I said when asked where I was from. No surprise, he wasn’t too familiar. After the basic pleasantries were exchanged, Carlos wasted no time getting started. He never removed his dark glasses when we went inside. I found that interesting.

The tour proceeded through the various areas of the building where different parts of the program are carried out. At Homeboy Industries, individuals from many circumstances and backgrounds, especially those with a history of gang affiliation, drug use, and incarceration, participate in an 18-month program in which they are paid to work in one of several social enterprises or other parts of the organization. During the program, these individuals are able to take advantage of numerous services, including social and legal help, educational counseling, mental health and substance abuse counseling, tattoo removal, vocational training, and other programs and lifelines that help individuals rebuild their lives in positive and productive ways. Social enterprises at Homeboy, which are regular businesses but with an aim to help and give people opportunities, include a bakery, catering services, electronics recycling, a silkscreen and embroidery shop, an award-winning café, and most recently, a dog grooming service.

Through all of these programs and enterprises, hundreds of people are able to be employed, finish their GEDs, get the counseling and legal help they need, make friends, and stand on solid ground — in many instances for the first time in their entire lives. As we walked through the building, we saw these activities and programs in action. We saw an anger management class was being held, which is a California parole requirement for many of the homies that Homeboy is authorized to offer. Other rooms were occupied by counselors and attorneys offering their services. There were even people walking around with bottles of 409 and rags wiping down walls and door handles that were already looking pretty clean. Sometimes people just need something to do, right? But people were moving about in swarms from place to place like passing time at a high school. I don’t know if that was a particularly busy day or what, but it was a happening place to be.

Our tour guide Carlos was a pretty popular guy. As he ushered us around, he was greeting and greeted by seemingly everyone. And since we were with Carlos, everyone was nice to us. Scratch that. They would have been nice to us anyway because that is how it is at Homeboy, but it helped to be there with Carlos. Giving dap to everyone was expected (good thing I was experienced!), but two or three separate times I was wrapped up in a bear hug by a complete stranger showing me love and thanking me for being there. Everyone welcomed me. Even though I was a visitor, never once did I feel like an outsider. Being totally honest, I am about as foreign of a character as you could possibly ever find in a place like Homeboy Industries. I cannot even begin to tell you. And even if it was obvious, no one cared. Everyone was friends. It was powerful to witness that reality in action. Not even in places where I think I “belong” do I recall feeling so welcome.

Upstairs, we went into a room to escape all the noise. The room had a large window that overlooked Homeboy Bakery, which occupies a section of the headquarters compound. You could look down there and see homies in hairnets moving carts of bread around and so forth. There, Carlos asked if he could tell us his story. It’s one you won’t often get to hear, so I’ll summarize it here for the record. If I confuse any details here, I apologize, but you’ll get the idea.

When Carlos was a young adult, maybe even just eighteen years old, he got wrapped up in some tragic events that charted the course for his life in terribly unfortunate ways. One night, Carlos was in the car with some friends cruising around the projects. In an instant, someone in the vehicle pulled a gun and shots were fired at a person standing on the street as the car passed by. The person collapsed, the car stopped, and people got out. The person with the gun who had fired the shots ran toward the person who had been shot, clearly with the intent to keep shooting. But Carlos intervened, tackling the person to the ground and forcing the weapon from their hands. The rest of the group got back in the car and drove off. No other shots were fired and no one else was injured, but the person on the street who had been shot did not survive. Within minutes, the police showed up, and it was Carlos who was holding the murder weapon.

I don’t remember all the details of the case nor the nuance of the laws Carlos described or the timeline of specific events. But I do recall something about an initial sentence of 15-20 years. Shockingly, the individual who had fired the gun and confessed to the murder received a lesser sentence. The driver of the vehicle received no prison time, and the other two individuals present ended up serving less than five years. Carlos, who one might see was the closest thing to a helper in the situation, received the heaviest sentence, presumably because he had the weapon in his hand when the police showed up. The injustice and tragedy of the situation plummeted Carlos into a despair most of us could never comprehend. The anger and hatred that rotted his soul upon entering prison made him volatile. After what I gathered to be a few violent encounters with other inmates, he was eventually transferred to the infamous Pelican Bay State Prison in California, one of if not the most notorious supermax prisons in America. At Pelican Bay, Carlos was relegated to what is called the Security Housing Unit, or SHU, where he lived in solitary confinement for the better part of an additional 20 years. Through all the controversy that surrounded California’s treatment of prisoners in the SHU and the policy reforms that followed (Google it if you want), Carlos was there for the worst of it. In total, Carlos spent around 40 years in prison —the entirely of his adult life to that time— and had been out probably close to two years. Carlos told us that the reason he wore dark sunglasses even indoors was not to appear gruff. He wears them because the many years in the SHU at Pelican Bay had permanently sensitized his eyes to light — a condition called photophobia. The darkness and isolation in which he languished for so long took a physical toll, and now the light of the outside world is too much.

When Carlos concluded his story (with many other details I either cannot recall or that do not matter for my purposes here), there was a palpable mood in the room. Me and the other couple I was with just sat there for a minute in processing mode. It is unlikely I will ever meet another human being who as experienced what Carlos has.

“Are you guys familiar with the phrase ‘mi vida loca’”? Carlos asked. None of us had heard that before except for maybe in the hit 1999 song of a similar title by Ricky Martin.2 Carlos proceeded to teach us that mi vida loca (which in Spanish means my crazy life) is something of a metaphor for a life devoid of hope and meaning. He told us that when someone refers to their crazy life, particularly in the context of southern California gang culture, it often suggests complete resignation. An extreme degree of hopelessness where you as a person don’t care whether you live or die. A profound acceptance of perhaps the worst fate known in the universe — one where you no longer feel you have the power to choose what becomes of your existence. This is more than just having a bad day and feeling sorry for yourself. This is the type of spiritual and emotional anguish so forbidding and all-consuming that it compels otherwise rational individuals to make decisions that most people could never even think of. It is what Carlos described as the underlying force that perpetuates gangs and violence and crime and abuse of the worst types in society. It is pure darkness.

Carlos also taught us that a mi vida loca mentality completely robs a person of their ability to think about what they want in life and out of life. Imagine a life filled with so much pain, grief, tragedy, and addiction that you no longer understand what it means to dream. “What do you want?” Carlos asked us. “Can you think of something?” The answer for me was an obvious yes, I could. But someone mired in the mi vida loca mindset loses their capacity to imagine a better life for themselves and others, which likewise disempowers and discourages them from any proactive and constructive attitudes and behaviors.

Consider this: Fr. Greg often refers to the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) index, which came from a study by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the 1990s that identified ten specific types of childhood trauma spanning the domains of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction.3 They are:

- Physical abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Physical neglect

- Emotional neglect

- Mental illness in the home

- Substance abuse in the home

- Incarcerated relatives

- Domestic violence

- Parental separation or divorce

A large amount of the population (about 36%) will never experience any of the ACEs (thank goodness), with a precipitous decline in the number of people reporting one or more.4 Ultimately, 17% of Americans report four traumas or more, and in the case of the people Homeboy Industries primarily serves, most have experienced all ten. It is a level of human suffering that people of privilege can scarcely comprehend. It truly is, as the phenomenon suggests, a crazy life.

It was in the context of mi vida loca that Carlos situated Homeboy Industries as a source of hope when all hope is lost for so many. At the time I took the tour, Carlos was just a few months away from completing the program. Serving as a tour guide was his job, and I learned that it was an honorable one. Tour guides are ambassadors of all the best parts of Homeboy. While in prison, Carlos had managed to complete an associate’s degree. Now, thanks to the help and encouragement he received at Homeboy, he was enrolled at a local Cal State campus to complete his bachelor’s degree in sociology. While in prison, all of Carlos’ family had died. His mother, brothers and sisters. He had no one left. But the community at Homeboy had become his family, as was evident in his paternal presence for so many homies as we walked around the compound (quite the contrast from the forced isolation at Pelican Bay). I observed firsthand his outlook, which despite everything he had been through, was purely positive. Where his eyes literally could not handle physical light, he was figuratively basking in the transformative rays of its abstraction. The hope he found at Homeboy had changed him, healed him even, and the gravity of such a mighty change is seldomly encountered. I hear about it, and I seek it, but rarely is it standing right in front of me. I think that is why Carlos’ story meant so much to me.

“Make no mistake” Carlos said as we were wrapping up the conversation and the tour. “It all starts with Father Greg.”

At the conclusion of the experience, which lasted a couple of hours, I was able to snap a photo with Carlos before we all parted ways. But I wasn’t ready to leave. I went to the Homegirl Café and ordered a breakfast burrito. As I waited for my order, I just sat at a table and continued to marvel at everything happening around me. One of the servers in the café kept checking on me to make sure I was okay. He even brought me a big chocolate chip cookie on the house. And that wasn’t just good customer service. It was singing the song of redeeming love. It was care for me as a companion on life’s journey. As underserving as I was (and am), everyone there deemed me worthy of their individual ministering, and I felt the love of God through them. I simply don’t get to witness things like that very often. Fact is, I spend a lot of time around people with a pretty good handle on life. I spend a lot of time around people who generally enjoy the blessing of having hope, purpose, a sense of their own agency, and the ability to dream of a better life with the capacity and wherewithal to make it happen. Spending time with the homies, even for a few short hours like I did, will show you that despite certain challenges and periodic inconveniences, there is certainly a lot we take advantage of. I realize again and again where I find myself in relation to wholeness, and I am humbled as I contemplate my blessings and good fortune — those underserved and indescribable and those I can attribute to striving my best to follow Jesus and the things he taught. I likewise recognize my own brokenness, sickness, greed, and pride. And despite my objectively elevated circumstances compared to my homies in Los Angeles, they are so much better than me. They are far more advanced in their abilities to bear one another’s burdens, mourn with those that mourn, and comfort those in need. There is still so much for me to learn, and I pledged that day to remain a student of goodness and improve how I treat those around me.

I could probably frame my experience studying Fr. Greg’s books and visiting Homeboy Industries as an exercise in discovering my privilege. But for now, I’ll frame it as an exercise in Fr. Greg’s central message: the power of boundless compassion, radical kinship, extravagant tenderness, and cherished belonging. I have felt a transformative power as I have allowed myself to learn about people and their experiences. I have become a far more sensitive person as I strive to exercise compassion for others and spare them unfair judgement. I feel joy as I remember key experiences where radiant goodness and humankindness and cherishing were showed to me and helped me heal my comparatively shallow wounds. Things like a warm meal delivered on our porch when we were sick. A neighbor forgiving me when I accidentally hurt their feelings. Friends sacrificing time on a Saturday morning to help me move. Someone standing up for me at work. Some of my students who, in their poverty, pooled their meager funds to buy me a birthday present. Another student who sewed a blanket for my newborn daughter. And my grandfather asking me whenever I saw him, “Who loves you?” To which I would respond, “You do, grandpa.” What I would give to hear him ask me that again. These are the moments, I decided, when I feel closest to God and feel his mercy — and when I extend whatever kindness and mercy I can to those around me in return.

I have no other declaration or invitation other than to say that there is hope and goodness in this frigid world. Around every corner there are helpers and healers, both those needing light and those offering it. I thoroughly enjoyed my visit to Homeboy, and hope it isn’t my last.

Learn more at HomeboyIndustries.org

References

- Homeboy Industries

- I have since discovered a 1993 film titled Mi Vida Loca directed by Allison Anders about gang culture in LA, but it is unclear if the name of the film came first and defined the phenomenon Carlos described (similar to the 2009 film Mississippi Damned), or if they named the movie after the phenomenon. Nevertheless, it’s a thing.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study, last reviewed June 14, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among U.S. Adults — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 17 States, 2022.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72, no. 26 (June 30, 2023): 693–698. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7226a2.htm.